I read with admiration Therese Gardner’s recommendations for books to check out this month or any month of the year. Following her lead, I wanted to recommend a few of my favorite recent reads, with a bias toward the talented writers here in Denver who happen to teach at Lighthouse.

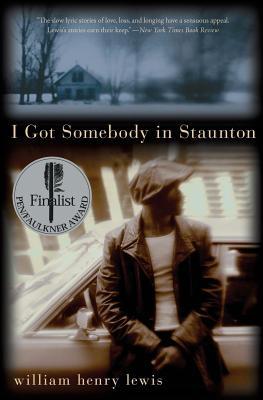

William Henry Lewis’s I Got Somebody In Staunton (Amistad/HarperCollins, 2005) is one of the most absorbing short story collections I’ve read in recent memory. A series of sweeping immersions in the lives of men, women, and young people, set in small towns and cities in the Southeast, up to DC, Virginia, NYC, Boston, Jamaica, and even to Denver. Each story is perfectly crafted, exploring aspects of family, relationships, loss, racism, memory, and solitude. One of my favorites, “In the Swamp,” follows a young man returning home with his fiancée for the funeral of a man, a father figure, he’s never told her about. The story suggests that families can be broken, and those broken parts can take up residence within us, making it especially hard to create any other kind of family. But we have to try. Another, “Crusade,” follows a former activist, retired from the NAACP, as he takes on a part-time job for FEMA, helping people who have survived natural disasters. He’s frequently overlooked by the younger people he works with. The story captures the alienation a person can feel when deep conviction is considered a weakness and “appropriateness” a strength: “His colleagues and supervisors, all of them younger than he, seem uninterested in his concerns. This seems necessary for the work they must do, so he has found a way to think of them as more driven than aloof, but when he is sitting in his boxers on the edge of the bed at night, a fierce bitterness wells up in him and he leans into the angry sleep of men who have smiled through too many decades of service.” In the title story, a history professor on his way to visit his dying uncle stops in a bar along the way and is convinced to give a young white woman a ride to Staunton, where his uncle lives. The tension builds as the story weaves in and out of cautionary tales his uncle has told him about the violent history in the Jim Crow south and, as the narrator puts it, “losing my Black ass,” driving through one fraught scenario after another, until they encounter a truck full of drunk white boys with guns. Each of these stories is gripping in its own way, mostly because each one feels utterly surprising and yet true. I’ve heard Lewis is at work on a series of novels right now and I can’t wait to read them.

William Henry Lewis’s I Got Somebody In Staunton (Amistad/HarperCollins, 2005) is one of the most absorbing short story collections I’ve read in recent memory. A series of sweeping immersions in the lives of men, women, and young people, set in small towns and cities in the Southeast, up to DC, Virginia, NYC, Boston, Jamaica, and even to Denver. Each story is perfectly crafted, exploring aspects of family, relationships, loss, racism, memory, and solitude. One of my favorites, “In the Swamp,” follows a young man returning home with his fiancée for the funeral of a man, a father figure, he’s never told her about. The story suggests that families can be broken, and those broken parts can take up residence within us, making it especially hard to create any other kind of family. But we have to try. Another, “Crusade,” follows a former activist, retired from the NAACP, as he takes on a part-time job for FEMA, helping people who have survived natural disasters. He’s frequently overlooked by the younger people he works with. The story captures the alienation a person can feel when deep conviction is considered a weakness and “appropriateness” a strength: “His colleagues and supervisors, all of them younger than he, seem uninterested in his concerns. This seems necessary for the work they must do, so he has found a way to think of them as more driven than aloof, but when he is sitting in his boxers on the edge of the bed at night, a fierce bitterness wells up in him and he leans into the angry sleep of men who have smiled through too many decades of service.” In the title story, a history professor on his way to visit his dying uncle stops in a bar along the way and is convinced to give a young white woman a ride to Staunton, where his uncle lives. The tension builds as the story weaves in and out of cautionary tales his uncle has told him about the violent history in the Jim Crow south and, as the narrator puts it, “losing my Black ass,” driving through one fraught scenario after another, until they encounter a truck full of drunk white boys with guns. Each of these stories is gripping in its own way, mostly because each one feels utterly surprising and yet true. I’ve heard Lewis is at work on a series of novels right now and I can’t wait to read them.

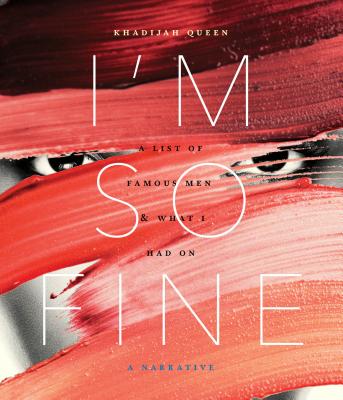

I’m a huge fan of Khadijah Queen’s I’m So Fine: A List of Famous Men & What I Had On, for its capturing of a time—the 1990s—and place (LA) that’s so alive in her work that you truly feel you were there. (And I happened to be not far from there at that time.) Of course, the collection moves beyond that time and place, but she first captures the burgeoning sexual power of the young speaker, the danger that can accompany that power, and then follows as the speaker grows older and pushes for safety. As she matures, she also moves geographically. “Edward Norton just stared he was on his cell phone going up the escalator at Port Authority I was going down & when we met in the middle he said you are gorgeous I was 36 & so NYC in a black turtleneck & salt-and-pepper curls & just starting to not be sad or afraid.” In the end she reaches a self-assuredness defined by personal and artistic strength. “Maybe I have to marry myself,” she muses. The cameos dazzle—from Chris Rock to Cuba Gooding Jr. to Robert DeNiro to Prince—but the poet in these stories is who you remember. This, for me, was the gateway drug to all of Queen’s remarkable work, from Black Peculiar to Conduit to Fearful Beloved. Her most recent poetry collection, Anodyne, is a must-read from Tin House.

I’m a huge fan of Khadijah Queen’s I’m So Fine: A List of Famous Men & What I Had On, for its capturing of a time—the 1990s—and place (LA) that’s so alive in her work that you truly feel you were there. (And I happened to be not far from there at that time.) Of course, the collection moves beyond that time and place, but she first captures the burgeoning sexual power of the young speaker, the danger that can accompany that power, and then follows as the speaker grows older and pushes for safety. As she matures, she also moves geographically. “Edward Norton just stared he was on his cell phone going up the escalator at Port Authority I was going down & when we met in the middle he said you are gorgeous I was 36 & so NYC in a black turtleneck & salt-and-pepper curls & just starting to not be sad or afraid.” In the end she reaches a self-assuredness defined by personal and artistic strength. “Maybe I have to marry myself,” she muses. The cameos dazzle—from Chris Rock to Cuba Gooding Jr. to Robert DeNiro to Prince—but the poet in these stories is who you remember. This, for me, was the gateway drug to all of Queen’s remarkable work, from Black Peculiar to Conduit to Fearful Beloved. Her most recent poetry collection, Anodyne, is a must-read from Tin House.

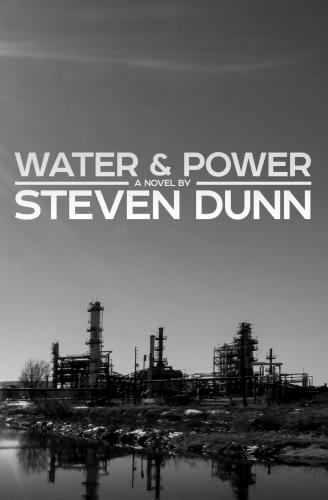

Steven Dunn’s Potted Meat was the first thing of his I read, the one that got me hooked. You can’t help but fall for the young speaker, growing up in a dying, addiction-riddled town in West Virginia. “My granddad finally teaches me his card tricks. He says to act kinda dumb while doing the tricks to make them chumps think they are smart. He says not to show anybody his tricks. I won’t, I promise. Ohh, I say, thats how you do it. Practice a lot first, he says, And once you get it down, you can always win some scratch off these suckas.” When he graduates high school, our narrator yearns to escape his family and this town. He and his friends find that escape by joining the Navy. Dunn’s next book, Water & Power, takes a documentary view of the military, and does so with a collage of interviews, field notes, casualty lists, slide presentations, posters, photographs, anecdotes, and more. The effect knocks you out. Early on, in boot camp, after withstanding a barrage of verbal, racist attacks about coming from West Virginia, the narrator gets up in the night to pee. “I walk in the head. A guy is trying to slit his wrist, disposable razor blood on sink. He sees me in the mirror. Oh, I say. That’s okay, he says, shitty razors.” That our narrator emerges alive but not unscathed is the gift that gives us this work.

Steven Dunn’s Potted Meat was the first thing of his I read, the one that got me hooked. You can’t help but fall for the young speaker, growing up in a dying, addiction-riddled town in West Virginia. “My granddad finally teaches me his card tricks. He says to act kinda dumb while doing the tricks to make them chumps think they are smart. He says not to show anybody his tricks. I won’t, I promise. Ohh, I say, thats how you do it. Practice a lot first, he says, And once you get it down, you can always win some scratch off these suckas.” When he graduates high school, our narrator yearns to escape his family and this town. He and his friends find that escape by joining the Navy. Dunn’s next book, Water & Power, takes a documentary view of the military, and does so with a collage of interviews, field notes, casualty lists, slide presentations, posters, photographs, anecdotes, and more. The effect knocks you out. Early on, in boot camp, after withstanding a barrage of verbal, racist attacks about coming from West Virginia, the narrator gets up in the night to pee. “I walk in the head. A guy is trying to slit his wrist, disposable razor blood on sink. He sees me in the mirror. Oh, I say. That’s okay, he says, shitty razors.” That our narrator emerges alive but not unscathed is the gift that gives us this work.

Other wonderful books by Black writers I’ve read lately and recommend: Memorial Drive, a harrowing and gorgeous memoir by poet Natasha Tretheway; Lot, a standout debut collection of stories by Lit Fest visiting author Bryan Washington (still to be read: Memorial); all of Alan Brooks’s comics; Brandon Taylor’s Real Life was a strong debut novel—looking forward to his story collection; and Transcendent Kingdom by recent visiting author Yaa Gyasi who, like Taylor, provides insight into the otherworld of American academic science programs, and some of the challenges of Black scientists trying to navigate them.