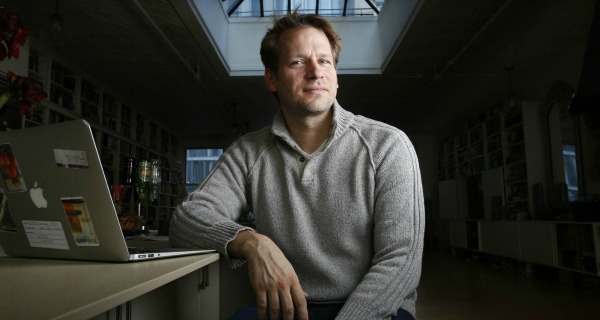

He’s the editor of the literary journal Freeman’s and executive editor of Literary Hub. He’s former editor of Granta and former president of the National Book Critics Circle. His books include How to Read a Novelist and The Tyranny of E-mail, as well as Tales of Two Cities and Tales of Two Americas, both anthologies of new writing about inequality in America, as well as Maps, his new collection of poems. His work has been translated into more than 20 languages and has appeared in The New Yorker, The Paris Review, and the New York Times, among many other publications. He is constantly on the move, promoting his journals all over the world, and his social media accounts are as popular for his photographs as they are for his book recommendations.

But Freeman is apparently a regular guy, if superhumanly devoted to books and the people who read and write them. As an editor, he’s always on the lookout for new voices, be they emerging writers or writers in translation. And as a reviewer, he ensures important books don’t get overlooked. In a recent profile in the Los Angeles Times, author Dave Eggers said:

I think of John as one of the preeminent book people of our time. He seems to know everyone, and has read every book, and reviewed most of them too. And meanwhile, he edits his magazine, and writes poetry, and apparently is some kind of semi-pro runner too. He would appear to be a hyperactive, high-intensity guy, but instead he does it all while being very low-key and unassuming. It’s impossible to overstate how important it is to have someone as generous and upstanding as John at the center of it all.

Lucky for us, Freeman is swinging through Denver on Friday. He’ll give a seminar on Denis Johnson and read from Maps afterward. He was generous enough to answer a few questions beforehand.

AR: First of all, I can’t believe I agreed to interview someone who has interviewed almost every great writer there is. What was I thinking? Can you give me any tips?

JF: Ha, well, just act as you do with a new dog: don't look into the whites of its eyes, approach slowly, extend your hand low and look away, and allow me to come to you.

In all seriousness, the assumption that we can elicit someone through pure interrogation is a symptom of our computer-driven celebrity obsessed age. Think of how many times we see, listen to, or watch someone getting interviewed. It's one of the most common forms of culture these days. Most people, though, explain themselves in stories. It takes a while to get to those tales sometimes, often a lot of meandering and making nice on behalf of the interviewer. So short answer, let's go get a coffee; I'll tell you everything.

AR: I’m going to take you up on that, since I have more questions than this forum would allow. In the meantime, I’m curious about your seminar on Denis Johnson’s poetry, which is geared toward writers of all genres. What can Johnson’s poetry teach writers of prose?

JF: I love Denis Johnson's poetry. To me, it's one of three or four great flowers of Whitman in the 20th century. (Johnson didn't seem to write much poetry after 1995.) I think everyone should read these poems because they're so funny and beautiful and touching and kind. They read like an attempt to create a cosmology of pain. For writers, they're a brilliant example of how to move from oneself outward to others. That's what we'll study in the workshop—the migration of empathy or, as Aleksandar Hemon would care to call it, the creation of a narrative field.

AR: Your own collection of poems, Maps, just out from Copper Canyon Press, has been described as “snapshots” and “layered exposures of time and place.” Were you thinking about photography as you wrote the poems?

As I wrote the poems in Maps, 2008-2017, I began taking photographs. All of us do now. With smartphones and Instagram. I was traveling a lot, too, and suddenly thought, what if I never go here again? Take a photo, Freeman! Plus, I was lonely. Taking photographs is one of the best cures to loneliness aside from jogging that I know. You look at the world through a detached engagement. I almost never take pictures of my face; it's much more interesting to me to look out, and doing this, you also have to learn to frame a shot. Poetry is very similar—it needs an aperture. Fiction, too. All narrative is in media res, come to think of it, you are cropping things out. The thing I like about photography is it doesn't really ask why—it just shows you things. So yes, as these poems became a manuscript, I tried to write poems that could do the same thing, feel like you were just watching something unfold, and maybe through layering of them, silently ask some questions. What do most maps leave out? Who draws them? How does drawing one change you?

AR: You’re renowned not only as a writer and a champion of writers, but as a “story hunter” with a talent for turning a cocktail-party-anecdote into an award-winning novel or story. Have you worked to develop an ear for writers’ untold stories? Or does it come naturally to you?

JF: I think my greatest gratitude here has to do with being the child of social workers. My dad was a story extractor. It often felt like getting cross-examined by a lawyer. No, no I didn't get home at 5 it was 6 because I was at the Dairy Queen! My mother was the classic case worker, who could create space in a conversation, and you just felt compelled to tell her things. Anyway, both of them believed in listening more than they spoke, my mother more so. I think being a slightly recessive personality, as one writer once described me, creates that space. I think asking questions helps, and then there is the ear thing. A new story or a story that needs telling has a vibration. You must do this as a writer: You see something in your head, a field at night with a cobalt sky over a house, one light on. It's vibrating in your head, and you grab it. That maybe gets you started. As an editor, when I'm listening, sometimes someone says something, and the reverse happens: I can see the iceberg below the comment or anecdote, moving slowly, displacing water.

AR: I love that, the idea of sensing other people’s icebergs. When you aren’t extracting stories from unwitting writers, what are you reading?

Right now I'm reading a lot of things. There are tons of new poets in America. To me, it's a golden time. Poets like Ocean Vuong, Solmaz Sharif, Robin Coste Lewis, Layli Longsoldier, Kaveh Akbar, and Danez Smith are doing so much to rejuvenate American poetry. If you're not reading poems you like today, you're not looking. But I also feel this immense memory hole developing, and poet after poet is just getting shoved in. So I've been reading J.D. McClatchy's 2003 edition of the Vintage Book of Contemporary American Poetry. Does anybody read Howard Nemerov anymore, or Carolyn Kizer, or Robert Hayden, or Jean Garrigue? I love William Stafford too. It's not like I'm saying, this is the real poetry—I hate that kind of exclusivism. But I like a lot of context. I'm also reading a lot of Aleksandar Hemon's work because I'm talking to him in Santa Fe this week, and a new novel by Luis Alberto Urrea, called The House of Broken Angels, which I'm reviewing. I've also been watching Gomorrah, the TV series, so I've dragged out Roberto Saviano's 2007 book, which is very different, and I'm reading that and marveling at the size and scale of the Camorra in Naples. Finally, I'm always reading a bit of Mary Oliver in winter because I find it feels essential in New York, to remember it's a season and not just a change in light.

For more information on John Freeman's upcoming craft class, Denis Johnson and the Migration of Empathy, click here. To register for his reception and reading, click here.

Lighthouse instructor Amanda Rea's writing has appeared in Harper's, One Story, Electric Literature, The Missouri Review, The Kenyon Review, The Sun, and elsewhere. She is the recipient of a Rona Jaffe Foundation Award, a Pushcart Prize, and the Peden Prize for Fiction.