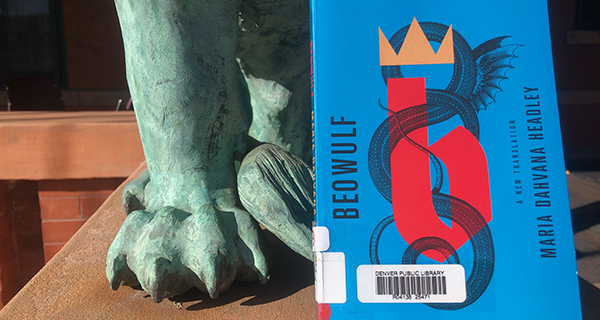

The first thing you’ve probably heard about the new Beowulf translation is that the translator, Maria Dahvana Headley, uses “Bro” to begin the story instead of “Listen,” or “Hark,” or Seamus Heaney’s “So.” You’ve probably also heard about her use of terms of like “hashtag” and contemporary cursing. At the very least, you’ve likely seen its gorgeous cover.

It all works, marvelously. Translating the classics can often be an ego-thing, and when it comes to the sweaty, shield-smashing epics like The Odyssey and Beowulf, a manly thing. So a lot has been noted about Headley’s feminist translation, her earlier novel adaptation of the story, and the “revisionist” looks she gives the female characters in the epic poem.

(I personally think every translation is a revision; how could moving from one language to another not be? Some translations are more creative than others, and sometimes they work, and sometimes they don’t. But the idea of the “literal” or “faithful” translation? As Headley’s narrator might say, “Bro, c’mon.”)

So Headley took a 1500-year-old, countlessly translated, epic poem about a hero and did two things: she turned it into a three-sheets-to-the-wind epic brag at the neighborhood bar, and she let all this manliness gain a consciousness, gave it some room to breathe, to let in some melancholy and doubt and knife-edge cocksuredeness and even some non-male perspective.

It’s a fun, rollicking combination.

We get modern nine-figure athlete bragging, as Beawulf intro’s himself to the poor Geats who have failed at vanquishing their decades-long tormenter, Grendel:

“I’m the strongest and the boldest, and the bravest and the best.

Yes: I mean—I may have bathed in the blood of beasts,

netted five foul ogres at once, smashed my way into a troll den

and come out swinging, gone skinny-dipping in a sleeping sea

and made sashimi of some sea monsters.

Anyone who fucks with the Geats? Bro, they have to fuck

with me. They’re asking for it, and I deal them death.”

We get the sadness that can only come from death, and striving against it:

"What had he hoped, the man who’d pressed

his people’s precious things into a cave beneath

the cape? All his keeping came to nothing.

First, the dragon killed the king, then the king

killed the dragon. Maybe a man’s might,

maybe he’s known to all as a warrior, but

Death has his number. No one knows

when it’ll be called, when he’ll have to walk backward

out of the beer-hall, exiled from life.”

We get a vanquished villain’s mother who’s righteously angry, not just inherently evil; she’s a “warrior-woman” and “outlaw” rather than an “Ogress” (Tolkien’s take) or “Monstrous hell-bride” (Seamey’s):

"Now his mother was here,

carried on a wave of wrath, crazed with sorrow,

looking for someone to slay, someone to pay in pain

for her heart’s loss."

And we get thrilling battle scenes:

"The grasp began

The tear that would take Grendel out, rendering him

a revenant in the hall he’d always reveled in.

His bones cracked, but he could not wrestle free

from the clasp, war-wedded to a war-bringer,

who clung like no human clung,

keeping him close."

And through it all? A poet’s attention to the sonic qualities of alliteration and slant rhyme:

"Beowulf stood tall, his iron shield upraised, armored

in his own fame, his helmet, his mail-shirt, his faith

firm only in Fate, a grit-god bearing brute weight,

beneath the rocky ledge."

The result is a book you tear through like a paperback thriller, a book you can’t help but quote from aloud to anyone and anything in the room with you. It transforms heroic braggadocio into a neccessary, sympethetic thing, a shield to keep at bay, if only (always) temporarily, the terrible forces sniffing at your front door. It makes queens and mothers powerful diplomats, melancholy realists, and righteous avengers. And with an eye ever towards the horizon (it's an epic, afterall), the rise and fall of kingdoms and families and beer halls, it humanizes and complicates the masculine, the feminine, and the monstrous.

Be sure to read Headley's introduction, too. It's an endearing dive into her choices as a translator, some context for Beowulf and its long history, and the underlying themes her translation teases out of the text.